Indoor Air Quality - General

On this page

- What is meant by indoor air quality (IAQ) for workplaces?

- Is indoor air quality (IAQ) a health and safety concern?

- What are indoor air contaminants?

- What symptoms are often linked to poor indoor air quality?

- Why do only some people seem to develop symptoms?

- What are some related health issues?

- Is air contamination the only cause of these symptoms?

- Can a person become sensitive to IAQ contaminants as time passes?

- Are there laws or guidelines for IAQ in non-industrial workplaces?

- Why can't I use chemical occupational exposure limits for indoor air contaminants?

- What should I do if I suspect that I am ill from poor IAQ?

- When should I start suspecting that IAQ may be an issue?

- Who should investigate?

- How should possible IAQ issues be investigated?

- What is a sample inspection walk-through checklist for IAQ?

- What information can the pattern of complaints reveal?

- What is a sample Assessment and Resolution flow chart for IAQ?

- What is an example of a health survey to help identify if IAQ is related to reported issues?

- What are the six basic IAQ control strategies?

- When should I seek professional help?

- How do I select an

d IAQ consultant?

What is meant by indoor air quality (IAQ) for workplaces?

Back to topIndoor air quality (IAQ) issues result from interactions between building materials and furnishing, activities within the building, climate, and building occupants.

The Canadian Committee on Indoor Air Quality and Buildings states that a healthy indoor environment is one that contributes to productivity, comfort, and a sense of health and well-being. Good IAQ will include air that:

- is free from unacceptable levels of contaminants, such as chemicals and related products, gases, vapours, dusts, moulds, fungi, bacteria, odours, etc.

- provides a comfortable indoor environment including temperature, humidity, air circulation, sufficient outdoor air intake, etc.

To maintain acceptable air quality, a workplace must maintain sanitation and recognize and correct water related issues quickly. Maintaining good air quality requires effort by both the building staff and occupants.

NOTE: This OSH Answers document focuses on non-industrial workplaces.

Is indoor air quality (IAQ) a health and safety concern?

Back to topIndoor air quality is an important health and safety concern for workplaces.

Common issues associated with IAQ include:

- Improper or inadequately maintained heating and ventilation systems.

- Contamination by construction materials, glues, fibreglass, particle boards, paints, chemicals, etc.

- Increase in the number of building occupants and time spent indoors.

When indoor air is not adequate, there may be issues such as:

- Increased health issues (e.g., eye and respiratory irritations) and, in rare cases, more serious health issues (e.g., carbon monoxide poisoning)

- Absenteeism and loss of productivity

- Strained relations between employees and employers

What are indoor air contaminants?

Back to topExamples of common indoor air contaminants and their main sources include:

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) – from building occupants and combustion of fuels such as gas and oil furnaces and heaters.

- Carbon monoxide (CO) – from vehicle exhaust brought into the

building buiding by air intakes. - Dust, fibreglass, asbestos, gases, including formaldehyde – from building materials.

- Vapours, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – from copying and printing machines, computers, carpets, furnishings, cleansers and disinfectants, solvents, pesticides, disinfectants, glues, caulking, paints etc.

- Dust mites – from carpets, fabric, foam chair cushions.

- Microbial contaminants, fungi, moulds, bacteria – from damp areas, wet or damp materials, stagnant water, condensate drain pans, etc.

- Ozone – from photocopiers, electric motors, electrostatic air cleaners.

- Other sources: tobacco smoke, perfume, body odour, food, etc.

What symptoms are often linked to poor indoor air quality?

Back to topIAQ issues do not affect everyone in the same way. When it is an issue, it is common for people to report one or more of the following symptoms:

- Dryness and irritation of the eyes, nose, throat, and skin

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Hypersensitivity and allergies

- Sinus congestion

- Coughing and sneezing

- Dizziness

- Nausea

People generally notice their symptoms after several hours at work and feel better after they have left the building or when they have been away from the building for a weekend or a vacation.

Many of these symptoms may also be caused by other health conditions including common colds or the flu, and are not necessarily due to poor IAQ. This fact can make identifying and resolving IAQ issues more difficult.

Why do only some people seem to develop symptoms?

Back to topAs with any other occupational illness, not all people are affected with the same symptoms or to the same extent. Some people may be more sensitive than others or have pre-existing health conditions. Some people may be exposed to more contaminants in the building than others and they may experience symptoms earlier than other people, or experience more severe symptoms.

As air quality deteriorates or the length of exposure increases, more people tend to be affected and the symptoms tend to be more serious.

What are some related health issues?

Back to topOccupants of buildings with poor IAQ report a wide range of health issues. Health issues and illnesses may develop soon after exposure, whereas exposure to other contaminants may produce health effects in future. Legionnaires’ Disease is an example of an illness caused by bacteria which can contaminate a building's air conditioning system.

A certain percentage of workers may react to chemicals in indoor air, each of which may occur at very low concentrations. Such reactions are often known as environmental sensitivities or multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS).

Some specific diseases have also been linked to or made worse by specific air contaminants or indoor environments, such as asthma being associated with damp indoor environments. In addition, some exposures such as asbestos and radon may not cause immediate symptoms but can lead to cancer after many years of exposure.

Is air contamination the only cause of these symptoms?

Back to topNo. Feelings of discomfort and illness may be related to any number of issues in the total indoor environment. Other common causes may include noise levels, thermal comfort (temperature, humidity, and air movement), lighting, ergonomics, and psychological aspects of work (e.g., stress, workload, etc.). It is important that all possible causes be investigated when assessing complaints.

Other OSH Answers documents on these topics include:

Can a person become sensitive to IAQ contaminants as time passes?

Back to topIt seems possible. Some people may not be sensitive to IAQ issues in the early years of exposure but can become sensitized as exposure continues over time.

Are there laws or guidelines for IAQ in non-industrial workplaces?

Back to topMany Canadian jurisdictions do not have specific legislation that deals with indoor air quality issues in non-industrial workplaces. In the absence of such legislation, the "general duty clause" applies. This clause, common to all Canadian occupational health and safety legislation, states that an employer must provide a safe and healthy workplace. Thus, making sure the air is of good quality is the employer's duty.

Several organizations* have published recommended guidelines for indoor air quality. For example, the Government of Canada has prepared a number of publications on air quality. Note that indoor air reference limits (IARLs) have been published by Health Canada, and other organizations. Other guidelines recommend that contaminants be kept at or below one tenth of their listed OEL.

In addition, IAQ is stated or implied in most building codes as design and operation criteria. Building codes and health and safety legislation in Canada generally refer to a version of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers* (ASHRAE) Standard 62.1 Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality (or previous versions), or other acceptable standards.

Please see the OSH Answers Indoor Air Quality Legislation for more details.

*We have mentioned these organizations as a means of providing a potentially useful referral. You should contact these organizations directly for more information.

Why can't I use chemical occupational exposure limits for indoor air contaminants?

Back to topThe concentration limits for contaminants that are specified in the health and safety legislation that are referred to as occupational exposure limits (OEL), threshold limit values (TLVs ®), or permissible exposure limits (PEL):

- apply to industrial workplaces where the worker composition (e.g., age and pre-existing conditions) is not the same as that for non-industrial workplaces,

- are based on a 40-hour work week for the lifetime of an industrial worker (e.g., worker at chemical manufacturing facility), and

- are set to protect workers from possible health-based hazards (e.g., eye and nose irritation) and are NOT fine lines between safe and dangerous exposures.

These limits are not appropriate for:

- control of air quality for non-industrial workplaces (e.g., offices or homes),

- control of community air pollution, and

- use by anyone who has not been trained in industrial hygiene.

Therefore, it is not recommended that "regular" occupational exposure limits (OELs) such as TLVs®, and PELs be used to determine if the general indoor air quality meets a certain standard. OELs use dose-response data which show the health effects of repeated exposure to one specific chemical. Similar data is not available for long-term, low-level exposures to a combination of contaminants as is the case for many IAQ situations.

What should I do if I suspect that I am ill from poor IAQ?

Back to topIf you think that you may be ill from IAQ issues, it is important to keep track of when you get your symptoms (aches, pains, headaches, etc.) and when they go away. This record will help your safety officer or health professional determine what the issue is related to. You may also wish to discuss your symptoms with your health professional to rule out any other medical conditions.

As with any other occupational health and safety concern, you can discuss your concerns with the health and safety representative, the health and safety committee, your supervisor, safety co-ordinator, industrial hygienist, or any other member of your company that is responsible for health and safety.

Your local government jurisdiction may also be able to provide information and

When should I start suspecting that IAQ may be an issue?

Back to topWhen there is an issue with IAQ, people may experience various health conditions that are listed above. Since many of the symptoms are very similar to what we feel like when coming down with a cold or the flu (influenza), it is often difficult to say for sure if indoor air is the cause of the symptoms.

However, it would be prudent to investigate IAQ if people develop these symptoms within a few hours of starting the workday and feel better after leaving the building, or after a weekend or vacation. In addition, if many people report similar symptoms, or if all of the people reporting symptoms work in the same area of a building, air quality should be suspected.

Who should investigate?

Back to topMany people may play a role in helping to resolve an IAQ issue including the building owner, employer, property manager, and occupants. Who conducts your investigation will depend on your workplace, but in general, you should have one person who is the leader, and perhaps a small team, including a representative from the health and safety committee, or the union, if appropriate. The expertise of many other people such as health and safety or building maintenance personnel, and the experience of everyone in the workplace will all be important in finding the root cause of your IAQ issue.

How should possible IAQ issues be investigated?

Back to topUnfortunately finding the source or cause can often be difficult. The steps taken may vary from situation to situation but will include:

- Conduct a walk-through inspection.

- Examine the complaints to see if there is a pattern.

- Inspect the ventilation system to make sure it is operating properly (e.g., the right mix of fresh air, proper distribution, filtration systems are working, etc.).

- Look for possible causes (e.g., source of a chemical, renovations, mould, etc.).

- Rule out other causes of the symptoms such as noise, thermal comfort, humidity, ergonomics, lighting, etc.

- Conduct a survey to help pin-point work sources and causes (see below for a sample survey).

- Consider help or air testing by a qualified professional.

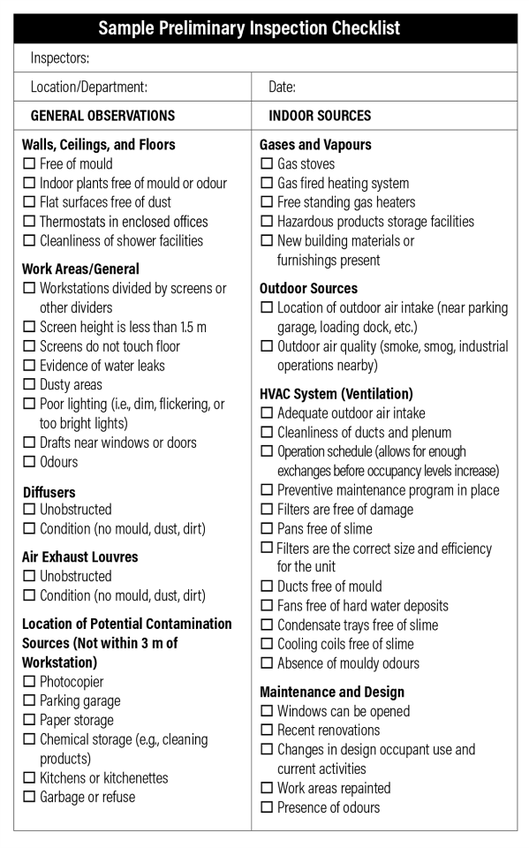

What is a sample inspection walk-through checklist for IAQ?

Back to topThe following is a sample inspection checklist. Adapt or modify this checklist to best match your needs.

What information can the pattern of complaints reveal?

Back to topExamining the pattern of complaints may help indicate what element should be examined further.

| Pattern of Complaint | Possible Source or Cause |

| Widespread – no pattern |

|

| Localized – reports are from 1 room or a single HVAC zone |

|

| Individuals |

|

| Symptoms begin at the start of the work shift |

|

| Symptoms get worse over a period of time (the day or shift) |

|

| Intermittent symptoms |

|

| Single event |

|

Adapted from: Alberta Government (2009). Indoor air quality tool kit.

What is a sample Assessment and Resolution flow chart for IAQ?

Back to top

What is an example of a health survey to help identify if IAQ is related to reported issues?

Back to topThe following is a sample of a questionnaire that could be used to help identify if an office or building has an indoor air quality problem.

- Use this questionnaire in consultation with a health and safety professional or other expert(s).

- Modify or customize this questionnaire to address the conditions and work practices at your workplace.

- Analyze the responses in consultation with an expert.

SAMPLE HEALTH SURVEY (Adapted from: Indoor Air Quality Health and Safety Guide, prepared by CCOHS)

What are the six basic IAQ control strategies?

Back to topThe Canadian Committee on Indoor Air Quality in Buildings recommends the following six strategies for controlling the quality of indoor air:

Source Management is the action of identifying, avoiding, isolating, or removing a source of air contamination. It is one of the most important strategies because it addresses root causes of IAQ issues. For example, policies should be implemented for the selection of carpets, furniture, and equipment that have low emission ratings of contaminants.

Local Exhaust involves the removal of point sources of pollutants before they can disperse into the indoor air by expelling contaminated air directly outside. Sites where local exhaust is used include restrooms and food preparation areas. Other locations where pollutants originate at specific points and can be easily exhausted include storage rooms and photocopying rooms.

Ventilation introduces outdoor air into a building to displace or dilute contaminants in the indoor air. Generally, local building codes specify the quantity (and sometimes quality) of outdoor air that must be continuously supplied to an occupied area. For activities such as painting, or in the event of chemical spills, a temporary increase in ventilation can help to dilute the concentration of noxious fumes in the air. In such cases, reducing or eliminating recirculated air is advisable. Ventilation should not be considered as a substitute for proper work practices and other measures that eliminate or control the original source of the pollutants. Ventilation is most efficient and effective when applied to a well-designed and managed facility.

Exposure Control includes adjusting the time and location of building occupancy to minimize expo-sure to intentionally released air contaminants. For example, the best time for stripping and waxing floors may be on weekends. This schedule would allow the floor products to off-gas over the weekend, reducing the level of odours or contaminants in the air when the building is occupied. This strategy may require adjusting ventilation rates which are often reduced during weekends and other unoccupied periods.

Air Cleaning is the capture of particles from the air. Various types and levels of particle filtration are normally included in ventilation systems. Gaseous contaminants can also be removed, but in most cases these types of systems are complex and expensive and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Education of the building occupants about IAQ is critical. People must be provided with information about the sources and effects of contaminants (including those under their control), and about the proper operation of the ventilation system. With this knowledge, they will better understand their indoor environment and can take steps to reduce their personal exposure and improve the overall IAQ.

When should I seek professional help?

Back to topIf the issue persists even after you have identified and corrected some issues, you may want to seek professional assistance. You may also require help if the issue requires immediate attention and your resources are limited, or if your investigation does not reveal possible causes.

How do I select an

Back to top

There are no legal requirements for a person to be designated as an indoor air quality consultant. It is the client's responsibility to find a competent consultant who is qualified by education, knowledge, and experience.

When hiring consultants, assess their professional background including education, professional credentials, the reputation of their firm, and, most important, demonstrated success in resolving similar situations. Ask for references.

See the OSH Answers Fact Sheet on Selecting and Hiring a Health and Safety Consultant for more information.

- Fact sheet last revised: 2022-12-12